by Adam De Gree

Have the political parties always held the positions they do today? Has the right moved further right, or the left further left?

The Republican Party of 2024 is far more liberal than the Democrat Party of the 1990s. With few exceptions, Republicans have consistently supported deficit spending, corporate welfare, and social welfare for decades now. This leaves many true conservatives looking like outliers.

To get a sense of just how much has been lost, it’s worth taking a look at one of the last consistently conservative American political movements: the Old Right.

The Old Right embodied many historically American values. Its members, who were both Republicans and Democrats, defended morality, tradition, and local government. Though they were—perhaps fatally—never organized into a single institution, they were unified in opposition to the progressive movement and its demand for an activist government.

In fact, the Old Right emerged in response to Teddy Roosevelt (pictured here) and his continuing influence in the Republican Party. In 1910, Roosevelt, though no longer president, tried to move the GOP to the left, calling for the party to support him as he opposed big business and proposed more federal regulation. Conservatives smelled a rat, and the Republican Party split, giving birth to the Old Right.

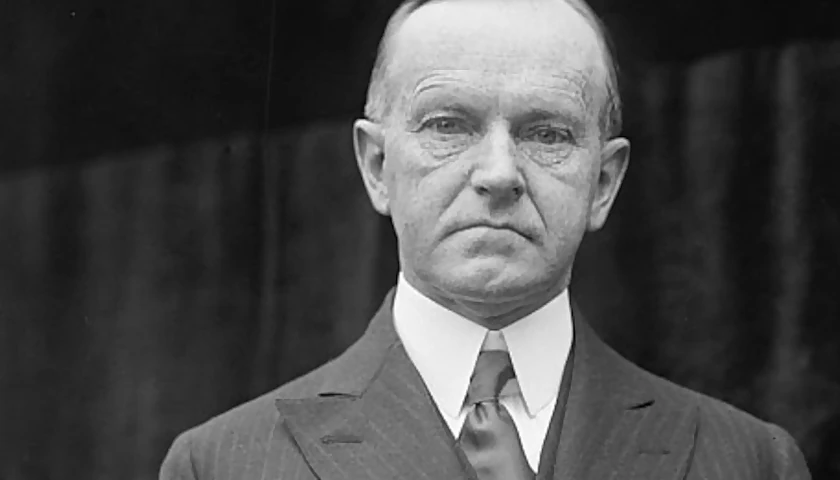

Perhaps the greatest electoral success of the Old Right came at the turn of the next decade with the election of Warren G. Harding as president. His vice president, Calvin Coolidge, succeeded Harding when the latter died in office in 1923.

Coolidge (pictured above) may have been the last president to take his constitutional role seriously. For example, under his administration, tax rates and government spending were reduced, and the budget was balanced. He believed that the economy should be run by the private sector, not the government, and he declined a second term, declaring that 10 years would be too long for one man to hold executive office.

Within a year of Coolidge leaving office, the stock market crashed, plunging the nation into the Great Depression. But this time, there was no great constitutionalist in the White House. Instead, there was Herbert Hoover, a Republican who promoted government intervention in economic life. In his own words, Hoover “met the situation with proposals to private business and to the Congress of the most gigantic program of economic defense and counterattack ever evolved in the history of the Republic.”

As we know, the most gigantic social and corporate welfare projects in American history did not lift the nation out of its crisis. Yet when Hoover’s opponent in the next election, Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR pictured here), won the election of 1932, he did not return to the proven strategies of the Old Right. Instead, he launched a raft of new programs that forever changed American life, and the Great Depression would not end for another decade.

It was opposition to FDR’s New Deal that brought much of the Old Right together. As their sharpest wit, H.L. Mencken, put it: “The New Deal began, like the Salvation Army, by promising to save humanity. It ended, again like the Salvation Army, by running flophouses and disturbing the peace.”

On the floor of Congress, the face of the Old Right was Robert A. Taft, who was often referred to as “Mr. Republican.” Like his fellow conservatives, Taft opposed military intervention abroad while denouncing economic intervention at home. His words in A Foreign Policy for Americans still hit home today:

We cannot adopt a foreign policy which gives away all of our people’s earnings or imposes such a tremendous burden on the individual American as, in effect, to destroy his incentive and his ability to increase production and productivity and his standard of living. We cannot assume a financial burden in our foreign policy so great that it threatens liberty at home.

Another famous member of the Old Right was Zora Neale Hurston, one of the great movers and shakers of the Harlem Renaissance. Hurston was fiercely opposed to the New Deal and worried that many Black Americans were becoming dependent on government programs. But rather than blame racism, she promoted the primacy of individualism:

Suppose a Negro does something really magnificent, and I glory, not in the benefit to mankind, but in the fact that the doer was a Negro. Must I not also go hang my head in shame when a member of my race does something execrable? [Likewise,] the white race did not go into a laboratory and invent incandescent light. That was Edison. If you are under the impression that every white man is an Edison, just look around a bit.

If there is a connecting thread tying together all the different members of the Old Right, individualism may just be it. Though they worked as critics, novelists, politicians, and businessmen, the members of this now-forgotten political force all jealously guarded their right to think and act according to their own authority.

It’s worth looking to their example to try to recover some part of the culture that has made America truly exceptional.

– – –

Adam De Gree is a classical educator and freelance writer. He teaches online history, literature, and government & economics courses for homeschoolers with Classical Historian. His writing has been published in venues including The Culture Crush, The Imaginative Conservative, and Partially Examined Life.

Photo “Teddy Roosevelt” by Samuele Wikipediano 1348. CC BY-SA 4.0. Background Photo “American Flag” by

Kevin Morris.